Microplastics in households occur more often than you think, and they can be reduced without extreme

Microplastics are a term that has become as familiar in recent years as plastic containers in a kitchen drawer. However, unlike them, we cannot see microplastics, which makes negotiating with them so difficult. When we talk about microplastics in the household, many people primarily think of cosmetics or glitter, but the reality is much broader: tiny plastic particles are generated during the normal use of items we've had at home for years, and they often release into the environment unnoticed. This is not a marginal issue—microplastics have been found in seawater, soil, food, and even indoor air. The question is not whether one will encounter them, but rather where and why they arise and how to reduce them in a way that is feasible even in a normal, hectic life.

To be clear: microplastics are generally plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters. Some of them were manufactured intentionally (typically microbeads in some older cosmetic products), but most are created by the breakdown and abrasion of larger plastics—exactly what happens during washing, cleaning, using textiles, packaging, or kitchen utensils. And this is where the household becomes a small "factory" for tiny particles that end up in waste, air, or water.

Try our natural products

Where microplastics in the household most commonly arise and why

One of the biggest sources is surprisingly synthetic textiles. Fleece, polyester, nylon, or elastane—materials that are comfortable, flexible, and quick-drying—release tiny fibers during wear and washing. Washing is a critical moment: the water flow, friction, and spinning can "comb out" microfibers from the textile, which then flow into wastewater. Although wastewater treatment plants capture some of these, they do not do so completely, and the captured sludge is often reused (for example, in agriculture), allowing particles to return to the environment. The issue of microfibers from washing is frequently discussed even in professional contexts; a good overview is provided by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) on plastics and microplastics, which summarizes why prevention is so important.

Another chapter involves plastic packaging and dishes, which are repeatedly heated, washed, and mechanically stressed in the kitchen. The older, more scratched, and more frequently exposed to heat the plastic is, the more easily tiny particles can be released from it. This does not mean that every plastic box is immediately "bad," but it is good to understand the context: heat and mechanical wear are crucial for particle release. Similarly problematic can be some types of non-stick cookware if the surface is damaged and flakes off—not only affecting cooking convenience but also what might end up in the food.

Microplastics can also be released from items one might not initially suspect: dish sponges, some synthetic cloths, cheap plastic brushes, but also decorations and trinkets made from soft plastics. In the bathroom, a mix of products and materials is added: disposable razors, plastic packaging, synthetic textiles (towels and bath mats with polyester blends), and even dust. Yes, even house dust is important—some microplastics spread through the air and settle on surfaces. Indoors, particles can be released from textiles, carpets, curtains, upholstery, or foam fillings.

Interestingly, microplastics in the household do not only "originate" there but are often brought in as well: in food packaging, on clothing from stores, in dust from outside, or in common consumer goods. And there's another strong source often mentioned only marginally in the household context: water. Microplastics have been found in drinking water in various parts of the world; the situation varies depending on the source and treatment of the water. An overview of the occurrence of microplastics in water and the food chain is provided, for instance, by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which has long been addressing this topic from a risk and uncertainty perspective.

Why microplastics are harmful and why they are increasingly discussed

With microplastics, two things often coincide: a high degree of uncertainty (because research is relatively young and methodologies are evolving) and simultaneously strong reasons for caution. Microplastics are problematic simply because they are practically ubiquitous and persist long-term. They do not decompose "into oblivion" in nature; instead, they gradually break down into even smaller particles. And the smaller the particles, the more easily they can spread and potentially penetrate organisms.

Harmfulness is usually described on several levels. The first is purely physical: particles can irritate tissues or accumulate in the digestive tract of animals. The second level is chemical: plastics can contain various additives (dyes, plasticizers, stabilizers) and can also bind other substances from the environment. The third level is systemic: microplastics are a symptom of overproduction and wear of plastics and their endless cycle between the household, waste, water, and soil.

In a domestic context, people are often most interested in what it means for health. Expert institutions tend to be cautious about categorical statements because data is still being collected on the long-term impacts on humans and the role of particle size, mode of exposure (inhalation vs. ingestion), and overall burden. Nevertheless, a reasonable principle holds: when it is possible to reduce unnecessary sources, it makes sense to do so—especially since measures often bring additional benefits (less waste, cost savings, a cleaner home, longer-lasting items). As the saying goes: "It's not about perfection, but direction."

To make it not just theoretical, a short example from everyday life suffices. In one household, there was a recurring issue over several months about why fine dust kept appearing on dark furniture despite regular cleaning. It turned out that the main "contributor" was an older synthetic carpet combined with a fleece blanket that often rubbed against the sofa. After replacing the carpet with a natural material and changing the washing routine for the fleece (less frequent, gentler program, full load), the amount of dust visibly decreased. It wasn't laboratory measurement of microplastics, but a practical experience: by reducing friction and fiber release, the home simply became cleaner—and that's an effect that can be noticed immediately.

How to reduce microplastics in the household and get rid of them in practice

The good news is that tips for reducing microplastics in the household don't have to mean radical life changes. Often it's about adopting a few habits and making smarter choices when shopping or maintaining items. It's important to focus on areas where the biggest load is generated: laundry, cleaning, kitchen, and bathroom.

In practice, a simple rule works: less plastic, less friction, less heat on plastics. For clothing, a big impact can be made just by washing synthetic materials more gently. It helps to wash at a lower temperature, choose gentler programs, avoid extreme spinning, and above all, wash with a full drum (because less friction between pieces of laundry can reduce fiber release). Those who want to go further can use special bags or filters for microfibers; their effectiveness varies, but as a practical barrier they make sense, especially for fleece and sportswear. It's also useful to think when buying: natural materials like cotton, linen, or wool are not without impact, but in terms of microplastics, they don't add plastic fibers to the water. And when synthetic makes sense (for instance, for functional layers), it pays to choose higher quality items with longer lifespans, as wear is one of the main triggers for particle release.

In the kitchen, it's worth monitoring the contact of plastics with heat. Heating food in plastic (especially in the microwave) is an unnecessary risk not only because of microplastics but also because heat generally accelerates material aging. Without major investments, switching to glass, stainless steel, or ceramics where food is heated and stored can help. For plastic containers, it's wise to discard those that are scratched, clouded, or deformed—this is usually a signal that the material has been stressed. Similarly, with kitchen utensils: plastic spatulas and spoons wear out over time, and if they show signs of "nibbling" or softening, it's better to replace them with wood, stainless steel, or high-quality silicone designed for high temperatures.

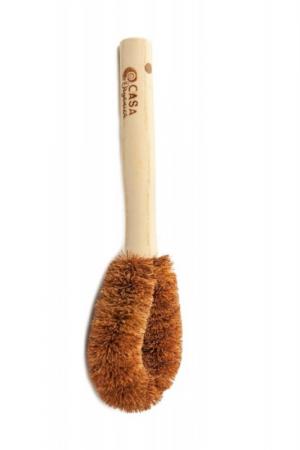

In the bathroom and during cleaning, a lot can often be accomplished with a simple swap of small items. Synthetic sponges and disposable cloths break down quickly, whereas natural alternatives (cellulose sponges, natural fiber brushes, cotton or linen cloths) have a longer life and release fewer plastic particles. Similarly, cosmetics without unnecessary plastic microbeads are now standard—in the EU, deliberately added microbeads in some products are restricted, but it still makes sense to read labels and choose products that are gentler on water streams. Additionally, switching to solid soaps, shampoos, or cleaning agents in refillable packaging reduces packaging plastic, which eventually turns into more waste.

And what does "getting rid of microplastics" mean when they are already in the home? It's impossible to avoid them completely, but it's possible to reduce their amount in the air and dust. Regular ventilation, vacuuming with a quality vacuum cleaner (preferably with effective filtration), and wet mopping help, as dry wiping can tend to stir up particles. For textiles, it's good to limit unnecessary "furry" synthetics in areas with a lot of seating and movement—like blankets on the sofa that rub against clothing daily. If they're already home, it's best to at least wash them sensibly and avoid over-drying in the dryer at high temperatures unless necessary.

For quick orientation, just stick to a few steps that are manageable without much planning:

Practical tips on how to reduce microplastics at home

- Wash synthetics more gently: lower temperature, gentler program, full drum, reasonable spinning; consider a bag or filter for microfibers with fleece.

- Do not heat food in plastic and discard scratched plastic containers; use glass or stainless steel for hot food.

- Swap small cleaning items: instead of crumbling synthetic sponges, choose natural brushes, cellulose, cotton, or linen.

- Limit "furry" synthetics in the living room (fleece blankets, cheap artificial throws), where they rub and dust a lot.

- Clean in a way that doesn't stir up dust: vacuum and mop wet, ventilate regularly.

The whole topic has another dimension that sometimes gets lost: microplastics are not just the "fault" of individuals. They are the result of how production, packaging, material availability, and what is considered normal consumption are set up. This makes it all the more important that changes at the household level are genuinely achievable and often have an immediate effect—fewer disposables, less dust, less unnecessary plastic in the kitchen. And when combined with pressure for higher quality products and better systemic solutions, it makes for a meaningful direction.

Perhaps the most practical thing is to ask a simple question: is it really necessary for everything at home to revolve around plastic that quickly wears out? In many cases, a few swaps are enough—a glass jar instead of a plastic one, a wooden brush instead of a crumbling sponge, higher quality clothing instead of quick synthetics—and microplastics will stop being an abstract threat. They will just become another reason to prefer items that last longer and make the home feel calmer and cleaner.