Why Diets Fail Even When You Follow Them and What to Do About It Long-Term

Rapid weight loss has something magnetic about it. Just a few weeks of "gritting your teeth," cutting out bread, sugar, or dinners, and the scale finally moves in the right direction. But then reality hits: returning to normal life, the first family celebration, stress at work, fatigue... and the pounds quietly come back. It's no wonder so many people ask, why diets fail and why the diet doesn't work, even when someone is "sticking to it." Maybe it's time to change the perspective: instead of another 30-day regime, try sustainable eating, not a diet. Not as a slogan, but as a practical change that can be lived long-term.

Why Diets Fail: They Aren't Made for Normal Life

Diets often promise clear rules and quick results. It sounds simple: forbidden and allowed foods, exact portions, ideally even a "detox." The problem is, a person is not an Excel spreadsheet. They eat in the context of emotions, family, work, sleep, health, and wallet. And this is where it becomes apparent why the diet doesn't work for most people long-term.

First: many diets rely on too large a calorie deficit. In the short term, this may mean weight loss, but the body is not naive. With long-term significant energy restriction, it naturally adapts – it slows down expenditure, increases hunger, mood worsens, and often sleep does too. Then a person doesn't feel "weak," but is biologically driven to eat more. There is a solid overview of how the body regulates hunger and energy on the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health website, which summarizes findings on sustainable weight loss over the long term.

Try our natural products

Second: diets are often based on prohibition. Forbidden foods often become the most tempting ones in the mind. Psychology is relentless here: the more something is "not allowed," the more it grows in attention. A vicious circle arises where a person tries to be perfect, fails with one cookie "slip," and instead of returning to normal, feels like "it doesn't matter anyway." And so, another portion, another day, another week is added. Why diets fail? Often because they work with the idea of 100% discipline, which is almost impossible to maintain in everyday life.

Third: many diets ignore that food is not just fuel. It's also culture, relationships, self-care. When eating is reduced to math and prohibition, joy disappears. And without joy, it cannot last long. It might sound trivial, but this moment is often pivotal: if the regime is based on suffering, it's just a matter of time before it ends.

And there's one more thing that's talked about less: rapid weight loss may seem like success at first, but it's often a mix of water, glycogen, and sometimes muscle mass. This doesn't mean that every rapid loss is automatically bad, but it's good to know that weight doesn't tell the whole story. The body needs time to adapt – and so does the mind.

Rapid Weight Loss: Why It Attracts and Why It Can Be Costly

It's not hard to understand why "quick results" sell. A person wants change immediately because they want to feel better right away. Moreover, people around notice the rapid loss, compliments come, motivation spikes. However, rapid weight loss often has a hidden cost that shows up later.

One of the most common costs is the yo-yo effect. Not as a personal failure, but as a consequence of the diet being temporary. If the regime is set to "endure" a month, what happens in the second month? The person returns to their original habits – and with them, the original weight returns. Sometimes even with a bonus, because the body "catches up" after a period of restriction. A credible summary of why long-term sustainability is key is offered by NHS, where the emphasis is on gradual changes and a realistic approach.

Another cost is a worsened relationship with food. When food is divided into "good" and "bad," a person starts eating with a sense of guilt. But guilt is not a good nutritional advisor. It often leads to secret overeating, eating quickly without awareness, or conversely to anxious control. The result? Instead of freedom, stress comes.

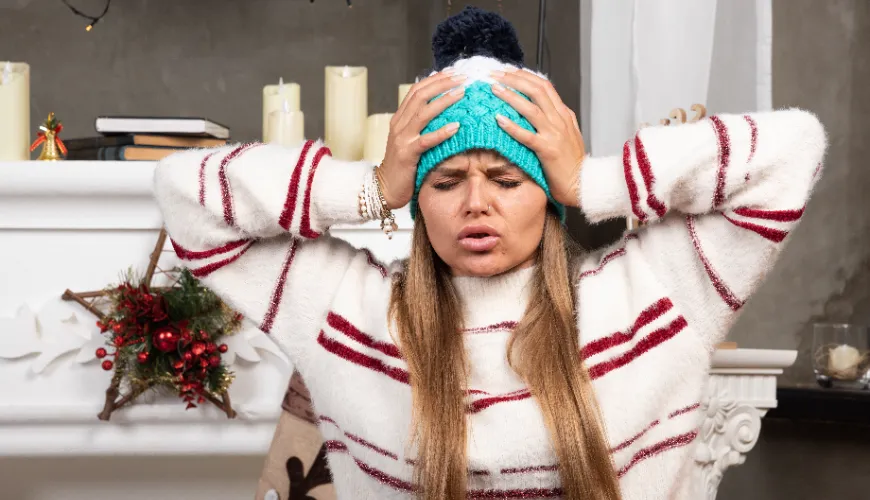

And then there's energy. Diets focused on quick results can lead to functioning on half-power: fatigue, irritability, poorer concentration. In such a state, it's hard to maintain movement, cooking, planning, and everyday responsibilities. Yet these "boring" things – regularity, meal preparation, natural movement – are fundamental.

This is well illustrated by a simple real-life example. Let's imagine Jana, who works in an office and has two children. She tries a popular regime promising minus five kilos in three weeks. The first days run on adrenaline: salads, protein bars, lots of coffee. The weight drops, people around praise her. But then comes a week when the children get sick, sleep is lousy, and work piles up. Jana doesn't have the strength to cook "diet" meals, reaches for bread and pasta that usually work at home. A red light goes on in her head: "I've messed it up again." And this is where the relationship with food and herself breaks. Not because Jana is weak, but because the regime wasn't built for a life that occasionally gets complicated. And it always gets complicated.

Maybe it's good to remember a simple sentence, often confirmed by nutritional practice: "The best meal plan is the one you can stick to on a Thursday evening when you're tired."

Sustainable Eating Instead of a Diet: What Works When You're Not Chasing Miracles

When you say "sustainable eating," it may sound vague. In reality, it's a very concrete approach: it's not about a short-term action, but about a way to eat so that it is long-term feasible, nutritious, and ideally more environmentally friendly. In other words: sustainable eating, not a diet.

The basic difference is that sustainable eating doesn't work with the mentality of "I'll endure now, then we'll see." It works with the question: what is realistic to do most days of the year? And that's surprisingly liberating because normality returns to the game. No food is "forbidden." Just some things make more sense more often and others less often.

Very often, it helps to stop focusing on individual "sins" and concentrate on a few pillars that make the biggest difference:

- Regularity and satiety: Meals that leave you hungry in an hour are a trap. It's helpful to think about having something in each main meal that satiates: proteins, fiber, quality fats.

- Fiber as a quiet hero: Vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fruits, seeds. Not for "detox," but because fiber supports satiety and digestion. A good overview of the importance of fiber and overall healthy eating is offered by the WHO, where diversity and the share of plant foods are repeatedly emphasized.

- Environment wins over willpower: When there's a bowl of fruit in sight at home and legumes in the pantry, it's easier to cook a normal meal. If there's just "something to snack on," snacking will happen. It's not character; it's the environment.

- Movement as a normal part of the day: Not as punishment for eating, but as care. Walking, stairs, cycling. The body doesn't move for a calculator, but to feel good.

Interestingly, sustainable eating often leads to weight adjusting "incidentally." Not always quickly, but more stably. And most importantly: there's a greater chance of maintaining the result because not just the numbers have changed, but the habits too.

This naturally includes the ecological dimension, which can be approached without extremes. When cooking more often with legumes, seasonal vegetables, and basic ingredients, it's not only nutritious but often cheaper and more sustainable. And when you add an effort to reduce waste (planning, using leftovers), it has an impact that goes beyond personal weight. It's not about perfection, but direction.

Perhaps the most important question is: what if one doesn't want to wait? What if change is needed immediately? Here it's worth distinguishing two things. The desire for change is legitimate. It's just good for it to be based on something sustainable. Rapid weight loss can be a short chapter, but it shouldn't be the whole story. Because if the goal is not only to lose weight but also to live well in that body, a regime is needed that won't fall apart at the first complication.

And this brings us back to the question of why diets fail. Not because people lack willpower. But because many diets are designed as temporary projects, while eating is an everyday reality. Sustainable eating is based on the fact that reality cannot be defeated, but it can be negotiated: a bit of planning, a bit of flexibility, plenty of normal food, and less drama.

In the end, what's pleasant about this approach is that it can start with a small step. Add one serving of vegetables a day. Swap some sweets for nuts and fruit, not because it's "forbidden," but because it gives the body more. Cook legumes twice a week. Stop waiting for Monday. And when a day doesn't go as planned? It's okay. The next meal is another opportunity, not a trial.

Perhaps this is the answer to why the diet doesn't work: because life isn't a diet. And the sooner eating stops being seen as a short course and starts being seen as long-term care, the greater the chance that results will finally stop disappearing as quickly as they came.